Have you ever looked up at the sky only to find yourself being frowned at by a cloud that is passing by? You are not alone. Spotting faces in inanimate objects – like the front of a car, the food you are eating, the facade of a building, or, indeed, different cloud shapes – is a common experience that has been scientifically recognised and is known as ‘pareidolia’.

Olaf Breuning, whose work has been exhibited widely from the Barbican Centre in London to the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo, has turned this phenomenon into a creative project. One glance at his Instagram profile reveals an extensive collection of faces that have emerged from the most everyday scenes.

It’s certainly no coincidence that his characters have resonated with people around the world, especially in the wake of the pandemic and induced social isolation. After what feels like one of the darkest years in our recent history, we don’t only build relationships with people – some of us may have found ourselves ‘in conversation’ with the objects around us. Who would have thought that Mrs Frankenpeach, Mr Greeneye, or Mr Pressure would save the day?

It needs to be simple but good

“I have always been on a mission to establish a line of communication that’s approachable and simple for the one looking at my art,” Olaf reflects. And not-so-hidden faces have been a key theme ever since he started his art practice.

This has proven to be a successful strategy for two reasons: they make his art accessible, and they are somehow “familiar” to us because our brains have a need to identify faces. As humans, we rely heavily on face recognition to understand and communicate, so it only makes sense that facial expressions capture our attention immediately – no matter if it’s a real or an illusory face.

“Back in 2013 when all my friends joined Instagram, I was very attracted to the visual appearance of it. But I didn’t want to show too much of my private life, so I decided to showcase the faces I see all over the place in my everyday life. I didn’t want to be a creep who just watches other people without posting anything myself. I thought that these faces would be good enough for the visual nature of the platform.”

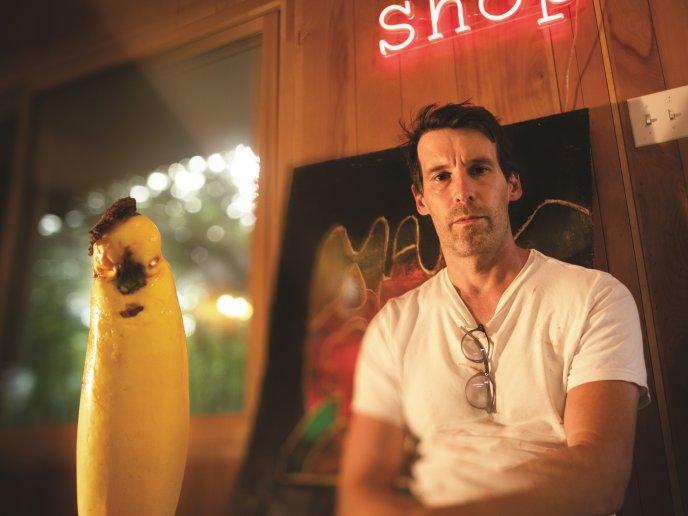

While some of Olaf’s creations appear accidental, like imperfectly shaped fruits and puddles of rain, others are deliberate and strategically placed, for example, his animated faces created from common household goods. No matter their source, shape, or witty names that always include the titles Mr or Mrs, Olaf’s faces have attracted a big community, including renowned institutions such as the National Gallery of Victoria in Australia, The Public Art Fund, and international art fairs such as Art Basel.

The ability to see faces everywhere he goes has also led him to work with the LA-based publishing house Silent Sound. Together, they released a book titled Faces featuring five hundred unique photographs of personas. Even commercial clients such as Apple and Gucci have found themselves drawn to Olaf’s playful world.

When life throws you lemons, look them in the face

It is no wonder that what had started as an artistic experiment to outsmart Instagram’s algorithm has made a profound impact internationally. But no one, not even Olaf, could have foreseen that his collection of faces would one day go hand in hand with the zeitgeist of a whole nation.

During the lockdown, his spontaneous bursts of creativity hit home – both literally and figuratively. Characters like Mrs Cuteandsoft, a calm-looking piece of banana, became more than just a silly meme. If anything, Olaf reminded us to find joy in the simple things around us, especially as many of us were forced to spend more time at home.

“Happiness is something we all need during the pandemic. I want to inspire people with my art, I want them to see the world differently and, most importantly, with a little distance and humour. Although it seems the world has lost humour these days, who is to blame?” he says.

A closer look at his art reveals that irony and a special sense of humour have been the main drivers of his work since the early nineties. While outwardly playful, Olaf’s work, whether it’s a theatrical installation, a photo collage, a painting, or a documentary, doesn’t shy away from contemporary and weighty topics such as the climate crisis, identity, death, and everyday horror mixed with authenticity and a touch of comedy.

Almost like a superpower, he can turn any circumstance, whether it’s dire or not, into a refreshing experience – even a pandemic. “In the beginning, I did not consider my Instagram posts as a part of my “serious” art. But over time, it became its own category with a simple concept. It won’t be difficult for me to continue doing it: I always see faces in things and I always have my iPhone with me.”

Playfulness thrives in carefully curated routines

“To be honest, I was more than happy to stay in one place and focus on my art and family, even though it feels strange to admit that while so much of the world is suffering,” Olaf says. “Luckily, I was used to solitude before Covid-19 hit the world. I don’t need anyone except myself at my studio, and for the moment, I am still happy to spend time here.

I always worked where I lived, and I guess the pandemic was not a new experience for artists in terms of working alone for most of the time. It’s a different experience for someone who leaves the house each morning to go to work. That being said, I am excited to be able to travel again soon – just a little,” he smiles.

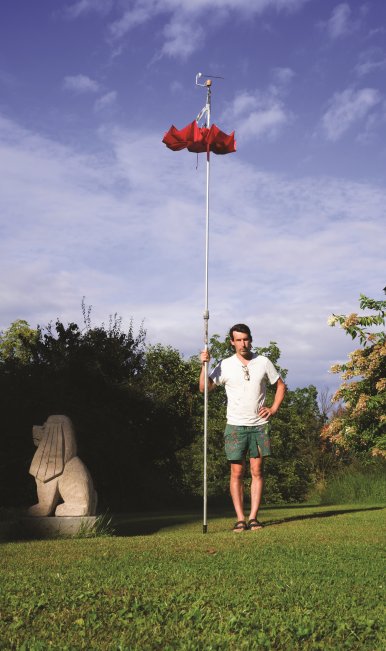

Five years ago, he moved to a mid-century house in Upstate New York, and he hasn’t regretted this decision. While cities turned into eerie places during the height of the pandemic, Olaf, his wife Makiko, and his three-year-old daughter Aka enjoyed mundane routines close to nature.

To find creative focus and to establish balance and wellbeing, every step between waking up at exactly 6:13am to prepare a Japanese breakfast and going to bed at 10:30pm is carefully curated. “It sounds really boring but somehow this simple routine is very nice. Of course, we also see friends at night or go outside to avoid feeling like being stuck in the longest Groundhog Day.”

Distributing joy into all corners of the home

But life at home is more than just simple schedules for Olaf. “Home should be a constant love affair. A cosy nest where good energies reside. A place that provides warmth and acts as a shelter in this crazy world, where problems can be reduced to sitting on the couch and drinking a glass of wine or cooking a nice meal in the kitchen.”

For someone who spends his life optimising every minute of the day, it is only natural to apply the same method when personalising the home with furniture and objects. For him it’s not about the picture-perfect set-up. He finds balance in moving around the house, which is why he created many ‘small pockets of joy’ that cater to his different needs.

“I always liked different rooms or tables for different tasks. I have a drawing table, a work table, an archive table, a mushroom table to clean mushrooms, and many more workstations. I also have two studios: one is for painting only and the other one is an office with an archive.”

Olaf’s concept of home hasn’t changed during the past 12 months, but he now fully embraces the daily order of things with an almost meditative mindset. With so much time spent at home, he has grown even more attached to his house: “I am someone who sees my house as a part of myself, a physical manifestation of who I am,” he admits.

Not travelling and staying put for such a long time made him sensitive to minor things that wouldn’t be obvious otherwise, like cracks in the marble and the squeaking sounds of doors. “These strange times forced us to finally face habits that were already on the horizon. On a positive note, people have learned to be modest and productive. And I am so happy to have exchanged the city jungle with a real forest jungle.”

Photos by Sergiy Barchuk, Faces by Olaf Breuning, Interview by Monique Schröder

Download the Life at Home Magazine